#98: "A more subtle form of greatness"_Part I

Why is love and service so hard in 2024 South Africa

Let’s scratch an awkward itch. Here’s the scenario: You love people. You read this not necessarily because you ‘enjoy’ the content but because you aspire to more. More love. Move hope. More change. What binds us all to this black-and-white experience is we share an expectation that there’s something beyond the shallow stories sold on social media?

But despite our aspirations we both battle with cognitive dissonance. It rolls around inside us like an upset stomach. You might not even be aware of yours despite feeling it’s nausea from time to time. But it's there. Gnawing away. A slippery guilt we can’t quite lay our hands on. Mother Terressa inspires and terrifies us. We love and hate Greta Thunberg. And if we’re truly honest we’re glad St Francis of Assai is dead. Easier that way. The last thing our guilt needs is ‘the great minimalist’ showing us what is actually possible with a life of abandoned love.

Let’s make it more South African. Traffic lights are a place of trauma? So is the Durban beachfront or anywhere the homeless hang out to make the twenty-eight Rand they need for shelters or their next fix of H. We avoid townships because empathy oozes out of us like a fragrance and that makes us feel trapped. Chained. Stuck to a chair labeled ‘stable income’. And yet despite all that ongoing trauma the little voice inside us hasn’t died yet. When we feel happy and free childish fantasies gallop through our mind that one day we might just tear off all these artificial constraints and finally chase a life of extravagant love?

The question this series of essays asks is why? Why is working out our hearts ‘calling’ so hard in 2024 South Africa. Welcome to Part I.

There is nothing like a high school reunion to unearth our deep, dark stories. Mine was on Friday. The inner workings of my brain describe ‘the itch’ well so I am happy to get naked to serve us. Two weeks before we met I chose what to wear. That’s almost more effort than I put into the wardrobe for both of my weddings combined. ‘Do I arrive with a coffee in my hand or not?’ fleetingly crossed my mind. And then, as the day approached, the scary question of ‘does the bump on the back of an old 1996 Landrover made me look seriously poor? became a valid area of concern.

A big part of me - let’s be generous and call it 90% - truly celebrates the life of service I share with my family. What is intellectually fascinating is how resilient the 10% of my brain is to all my efforts to kill the lie that my life choices make me an absolute fool. It seems at the root of our insecurities is the all-important question - what is greatness?

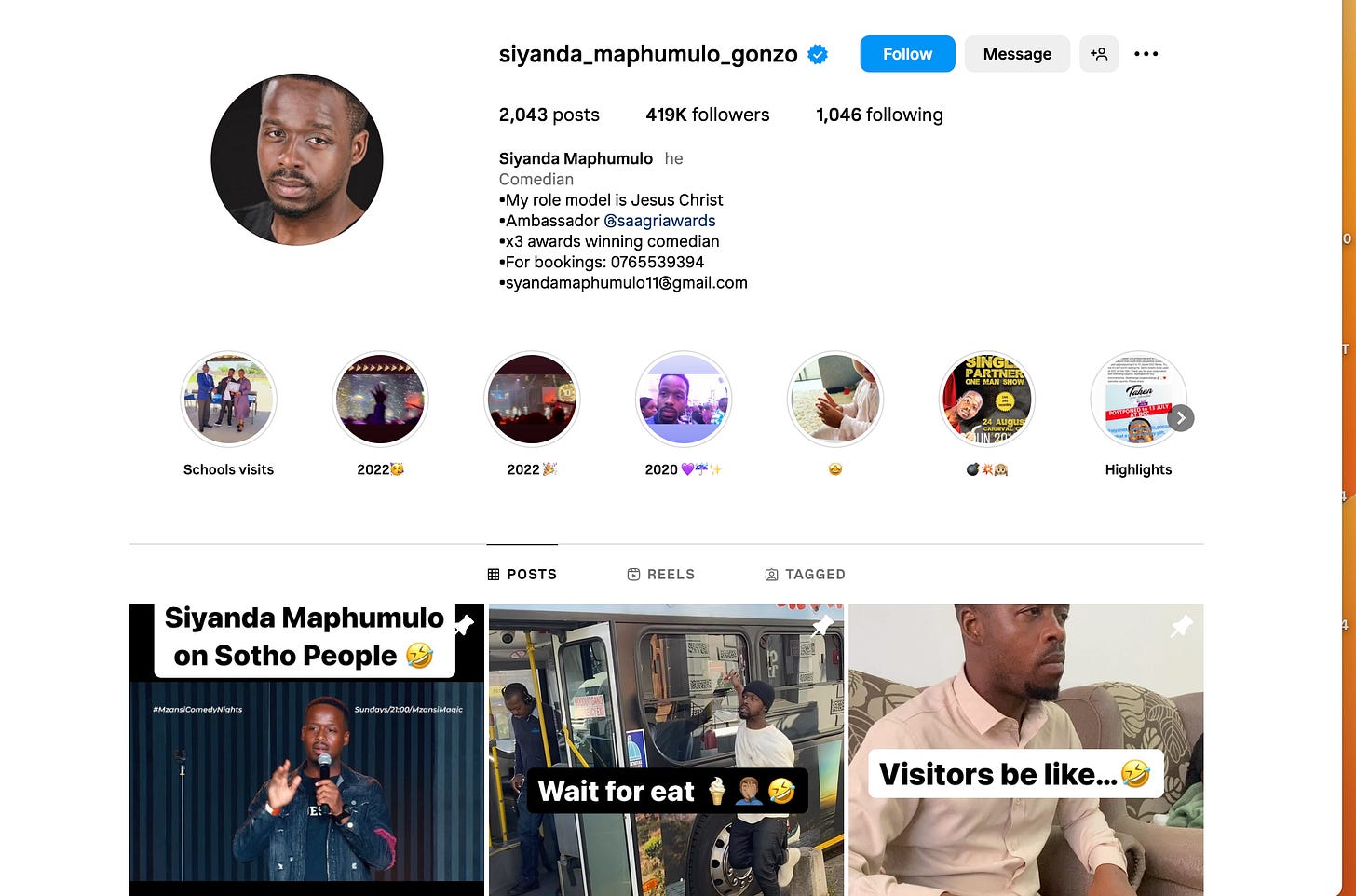

I sat with the comedian above the other day for work. He is huge in KZN. 412,000 followers on Instagram. At the top of his Instagram bio reads - ‘My role model is Jesus’. Normally I cringe at kak like that but seconds into our conversation I knew I was talking to someone different. “2,000 years later…”, he said, “and people are still finding truth from Jesus’ life… you can’t fake that kind of relevance…”

Huh… My academic training teaches me to be curious on my good days and aggressively critical on my bad. Plus, I have an anti-religion bend which makes me hunt hypocrisy and yet still, somehow, that gentle comedian’s words got to my heart in a way no polished sermon could. And I have to be honest, I repented. Changed my mind. Right there on the spot I reframed my view of greatness.

There’s lots of weirdness when it comes to Jesus. The cross. The God-man anomaly. Sweating blood. But in 2024 Jesus’s refusal to be famous could be considered his weirdest. 15,000 people gathered to hear him talk and he ignores them (see Sermon on the Mount), walks away, sits His arse down on the dirty grass and shares his life with his friends instead (not the crowd in case you missed it). Kids. Widows. Orphans. Jesus neatly defines greatness in those moments with his friends and still, 2024 years later, most of us would agree with him. What set Him apart unlike us is He actually followed through. Like Francis of Assai and Mother Teresa and Gretta he somehow broke through the veil of cultural conformity and lived a life of explosive freedom. The important question these essays ask is how?

But before we have any hope of answering that question we need to go down. Subterranean. As hard and fast as possible to the root of the problem. Here are my three reasons why His example is so hard to follow:

One: We don’t love ourselves.

Damm, that is direct. But let’s cut to the chase. It’s just scaffolding? All our money, cars and fame. They’re props. Masks and bandages hiding us broken humans who just want to feel safe in a dangerous world. That’s not a criticism. It is probably my greatest truism. It might be the greatest of all human truths. If we felt loved and accepted, naked and unashamed, we would feel no need to hide and cover ourselves with ill-fitting garments.

But we don’t love ourselves. Trauma ensures that. A couple of bad falls and unsuspecting lies get comfortable in our minds. You might not be even aware they’re there. Bashing you around all day long with their unkind words. And because we don’t love ourselves we believe others don’t love us either. And so for pure survival, we scrape together some sense of security from the flimsy stories we consume every day without thinking.

Two: We’ve defined success as greatness incorrectly, and we know it

I think in the bottom of our hearts and the back of our brains we all know the highest success a human can achieve is being a good husband/wife/partner/parent or friend? It seems without that bedded down even radical service lacks a foundation. The brilliant social commentator Prof Scott Gallowway synthesizes why in his book Algebra of Happiness. He neatly explains “Success is who you die with”. Genius.

But despite the inevitability of our final moment. The weakness of our minds. The obvious frailty of our human condition we desperately resist preparing for it with any sense of simple pragmatism because being a good spouse, parent or friend just seems too mundane. Too modest. Why?

There are 3,700,000 new videos loaded onto YouTube each day. And 1,000,000,000 are watched. Yup, a billion. Most of the content is about me and you. It’s explainers. Tutorials. Interviews, podcasts, life hacks, webinars and skits which bend our brains a bit more each time we watch.

Below is a helpful little image illustration of how. Consider it a dipstick into the billions of humans plugged into the internet on the 22nd of November 2022. Using the filter below they’ve predicted job aspiration. Six of the top ten are a mirror of our most dominant stories - writers, dancers, Youtubers, actors, influencers, and singers. One aspires to service - a teacher.

There’s a genuine tyranny to being compared to the 7 billion humans on the planet. Constantly having to measure our ‘greatness’ against theirs. Constantly having to struggle against those deep existential questions inherent to the human condition. I think Alan de Botton might be right, that pressure can be maddening until we confront it head-on.

Finally: We lack the discipline to change.

We’re going to colonize Mars before we understand how the human brain works. Billion of nerves holding multiple different people inside one head. There are memories in there somehow. Traumas. Stories. Expectation. Unruly, weird and fascinating ideas locked into an organic network so complex neuroscientists say our understanding is still stuck in the seventeen hundreds compared to the other areas of modern medicine.

And yet with all that unfathomable complexity the ‘sane’ and ‘responsible’ among us leave reframing our view on greatness to the occasional podcast…? Yes, we lack discipline.

My Dad started a business in a moldy one-meter by one-meter room in our garden. On the inside of the room’s wooden door was an A2 poster printed on cheap paper in just black and white. There were thousands of sheep on that poster. All of them head up and happy, bahahhing obedient, comforted by the closeness and momentum of their community as they headed together for the edge of a cliff. My dad took a highlighter, it was luminous blue, and he used that highlighter to mark out for himself the one sheep in the center of the herd headed the wrong way. It’s thirty-five years later and I can still see that tiny sheep in the crowd. Head down. Struggling. Straining against a cultural torrent that took everything he/she had to make an inch in the right direction.

But we binge-watch series. They pile up like plastic trophies. Modern Family. Grey’s Anatomy. Friends. Weeks pass and we pretend not to be shocked when somehow we’ve suddenly made it to Season 5, Episode 16 of something we have watched before (no judgment here, we’re on Season 3, Episode 18 of Gray’s Anatomy).

In their seminal meta-analysis of 144 research papers on Narrative Transporation, Van Laer et al (2014) show that once immersed in a story our “beliefs, attitudes, and intentions are altered voraciously”. In other words, we change. We believe stuff we otherwise wouldn’t. Right now I think like Dr. Mac-Steamy (Grey’s Anatomy reference) and you think like whoever you are watching; and for the awake that that is a valid area of concern. What attitudes are we binding ourselves to in those endless hours of brainwashing? If it is anything other than Ted Lasso the sad truth is that it is probably cerebral conformity with cultural stories around our throats that we hate.

We need to work towards a more “subtle form of greatness”. That’s a great line. Don’t give me credit, it is Alan de Botton’s as well. But if we want it we cannot afford to be docile…

Stay tuned for Part II.

PS: St Francis is the ‘fool’ in the picture above. If we’re looking for a point of reflection from today’s pieces he’s probably a good starting point. Born of a rich property merchant his courage still quivers around us today.